On The Junkheap as Ur-Symbol of Postmodernity

An excerpt from my forthcoming book "Hypermodernity & The Return of the Gods" (Ikonic Books, 2025)

Monchengladbach (1967)

The German philosopher Oswald Spengler borrowed the concept of the “Ur-symbol” from Goethe’s theory of the metamorphosis of plants. The Ur-symbol is a kind of Platonic Idea that confers synthetic unity upon the manifold of any given biological or cultural phenomenon. For Goethe, the Ur-symbol of all plants is the Idea of Leaf, since every individual part of a plant is a transformed leaf. Break open an orange and what do you see? Transformed leaves.

Spengler applied the concept to nine different civilizations, each of which has its own Ur-symbol. The Greco-Roman Ur-symbol, for example, is the Body, since all of its culture-forms are expressions of the near, the tangible and the tactile. The Magian (or Abrahamic) Ur-symbol is the World-as-Cavern, in which the entire cosmos is thought of as being enclosed inside of a cave. Hence, the Pantheon, as he says, is actually the first mosque, for the World-as-Cavern is entirely alien to the Greco-Roman world feeling, which admits of no interiority whatsoever. The Faustian Ur-symbol is Infinite Space, which is expressed most vividly in our Gothic cathedrals and in our four fundamental forces in physics. The basic a priori dichotomies of the sciences for each of the three are, respectively: form / matter, substance / attribute, force / mass.

With respect, then, to my idea of the three modernities—Modernity, Postmodernity and Hypermodernity—I see each of them as having its own unifying Ur-symbol, giving each epoch its own internal structural unity. The basic map looks like this:

MODERNITY: 1860-1945

Ur-symbol: The Hyperdimensional Object

The Body Electric: electricity

Dominant Media: telegraph / telephone / radio

Precedental War Events: Napoleonic Wars / World War I

POSTMODERNITY: 1945-1995

Ur-symbol: The Junkheap

The Body Electric: electronics / analogue

Dominant Media: film / television

Precedental War Events: World War II / Vietnam

HYPERMODERNITY: 1995-present

Ur-symbol: The Multiverse

The Body Electric: digital

Dominant Media: Internet / cell phones / computer

Precedental War Events: First Gulf War, 9/11, Middle Eastern Campaigns 2003-2022

In the present essay, I am only discussing the Ur-symbol for Postmodernity, which is The Junkheap. Nearly all of the art and literature which appears during the years 1945-1995 presuppose the Junkheap as their Morphogenetic Culture Field. It is an a priori metaphysical structuring principle that guides, governs and shapes all cultural phenomena during this time.

The Junkheap as an iconotype is that pile of deconstructed signifiers that have come dis-attached from their Lacanian quilting points (points de capiton) within the West’s metaphysical form fields. The art of Mark Rothko during the 1950s, in particular, displays what I have termed the “semiotic vacancies” left behind in the absences at the heart of the ontological center of the Western mind. During WWII, Europe is turned into rubble on the physical plane but on the metaphysical plane, it becomes rubble also. Absolutely anything written in France in or around the year 1968 displays the Junkheap as the structuring—or rather de-structuring—scaffolding (indeed, texts like Deleuze & Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus or Reiner Schurmann’s Broken Hegemonies, or Jaques Derrida’s On Grammatology are all philosophical junkheaps). Since the Junkheap was produced during the war, we will start there with an example from W.G. Sebald’s On the Natural History of Destruction in which he discusses the brutality of the Allied firebombings of German cities:

Another five minutes later, at one-twenty A.M, a firestorm of an intensity that no one would ever before have thought possible arose. The fire, now rising two thousand meters into the sky, snatched oxygen to itself so violently that the air currents reached hurricane force, resonating like mighty organs with all their stops pulled out at once. The fire burned like this for three hours. At its height, the storm lifted gables and roofs from buildings, flung rafters and entire advertising billboards through the air, tore trees from the ground, and drove human beings before it like living torches. Behind collapsing façades, the flames shot up as high as houses, rolled like a tidal wave through the streets at a speed of over a hundred and fifty kilometers an hour, spun across open squares in strange rhythms like rolling cylinders of fire. The water in some of the canals was ablaze. The glass in the tram car windows melted; stocks of sugar boiled in the bakery cellars. Those who had fled from their air-raid shelters sank, with grotesque contortions, in the thick bubbles thrown up by the melting asphalt. No one knows for certain how many lost their lives that night, or how many went mad before they died. When day broke, the summer dawn could not penetrate the leaden gloom above the city. The smoke had risen to a height of eight thousand meters, where it spread like a vast, anvil-shaped cumulonimbus cloud. A wavering heat, which the bomber pilots said they had felt through the sides of their planes, continued to rise from the smoking, glowing mounds of stone. Residential districts so large that their total street length amounted to two hundred kilometers were utterly destroyed. Horribly disfigured corpses lay everywhere. Bluish little phosphorous flames still flickered around many of them; others had been roasted brown or purple and reduced to a third of their normal size. They lay doubled up in pools of their own melted fat, which had sometimes already congealed. The central death zone was declared off-limits in the next few days. When punishment labor gangs and camp inmates could begin clearing it in August, after the rubble had cooled down, they found people still sitting at tables or up against walls where they had been overcome by monoxide gas. Elsewhere, clumps of flesh and bone or whole heaps of bodies had cooked in the water gushing from bursting boilers. Other victims had been so badly charred and reduced to ashes by the heat, which had risen to a thousand degrees or more, that the remains of families consisting of several people could be carried away in a single laundry basket.

Turning now to literary examples, this is from J.G. Ballard’s 1984 Empire of the Sun:

The canister had burst on impact…Around him, on the floor of the culvert was a ransom of canned food and cigarette packets. The canister was crammed with cardboard cartons, and one had broken loose from the nose cone and scattered its contents over the ground. Jim crawled among the cans, wiping his eyes so that he could read the labels. There were tins of Spam, Klim and Nescafe, bars of chocolate and cellophaned packs of Lucky Strike and Chesterfield cigarettes, bundles of Reader’s Digest and Life magazines, Time and Saturday Evening Post.

And from another WWII novel, here is Thomas Pynchon’s parody of Kabbalistic initiation rites from Gravity’s Rainbow (1973):

In the first room: a hypodermic outfit has been left lying on a table.…In the second antechamber is an empty red tin that held coffee. The brand name is Savarin...In the third, a file drawer is left ajar, a stack of case histories partly visible, and an open copy of Krafft-Ebing. In the fourth, a human skull. His excitement grows. In the fifth, a Malacca cane…In the sixth chamber, hanging from the overhead, is a tattered tommy up on White Sheet Ridge, field uniform burned in Maxim holes black-rimmed as the eyes of Cleo de Merode…At the seventh cell, his knuckles feeble against the dark oak, he knocks…She waits for him in a tall Adam chair, white body and black uniform-of-the-night.

And from William Gibson’s classic 1984 novel Neuromancer (which virtually foresaw the entire hypermodern world within which we now find ourselves living):

The door swung inward and she led him into the smell of dust. They stood in a clearing, dense tangles of junk rising on either side to walls lined with shelves of crumbling paperbacks. The junk looked like something that had grown there, a fungus of twisted metal and plastic. He could pick out individual objects, but then they seemed to blur back into the mass: the guts of a television so old it was studded with the glass stumps of vacuum tubes, a crumpled dish antenna, a brown fiber canister stuffed with corroded lengths of alloy tubing. An enormous pile of old magazines had cascaded into the open area, flesh of lost summers staring blindly up, as he followed her back through a narrow canyon of impacted scrap.

And now for some examples from postmodern art. This is the Auschwitz Demonstration (1968) of Josef Beuys:

Robert Rauschenberg’s Buffalo II of 1964:

And his Monogram of 1954-59:

Now it is not as though the breaks between these three epochs are abrupt discontinuities, since postmodern forms continue to appear—though their status is minimized to function as organelles within the larger body of the hypermodern organism—inside the epoch of hypermodernity as atavistic carry-overs. Here is Christian Boltanski’s No Man’s Land of 2010:

And Anselm Kiefer’s Sternen Fall / Shevirath ha Kelim from 2007:

In the Kabbalistic myth of the Breaking of the Vessels (Shevirath ha Kelim), the 10 vessels of the Sephiroth could not receive the impact of God’s light at the beginning of Creation and so were shattered in the process and became shards known as “Qlippoth,” which are the fragments of the material world, or as Thomas Pynchon puts it in Gravity’s Rainbow: …a process by which living souls unwillingly become the demons known to the main sequence of Western magic as the Qlipoth, shells of the dead.” (And likewise Doris Lessing in her 1980 science fiction novel terms the earth “Shikasta,” meaning in the alien tongue which she invents “the broken one”).

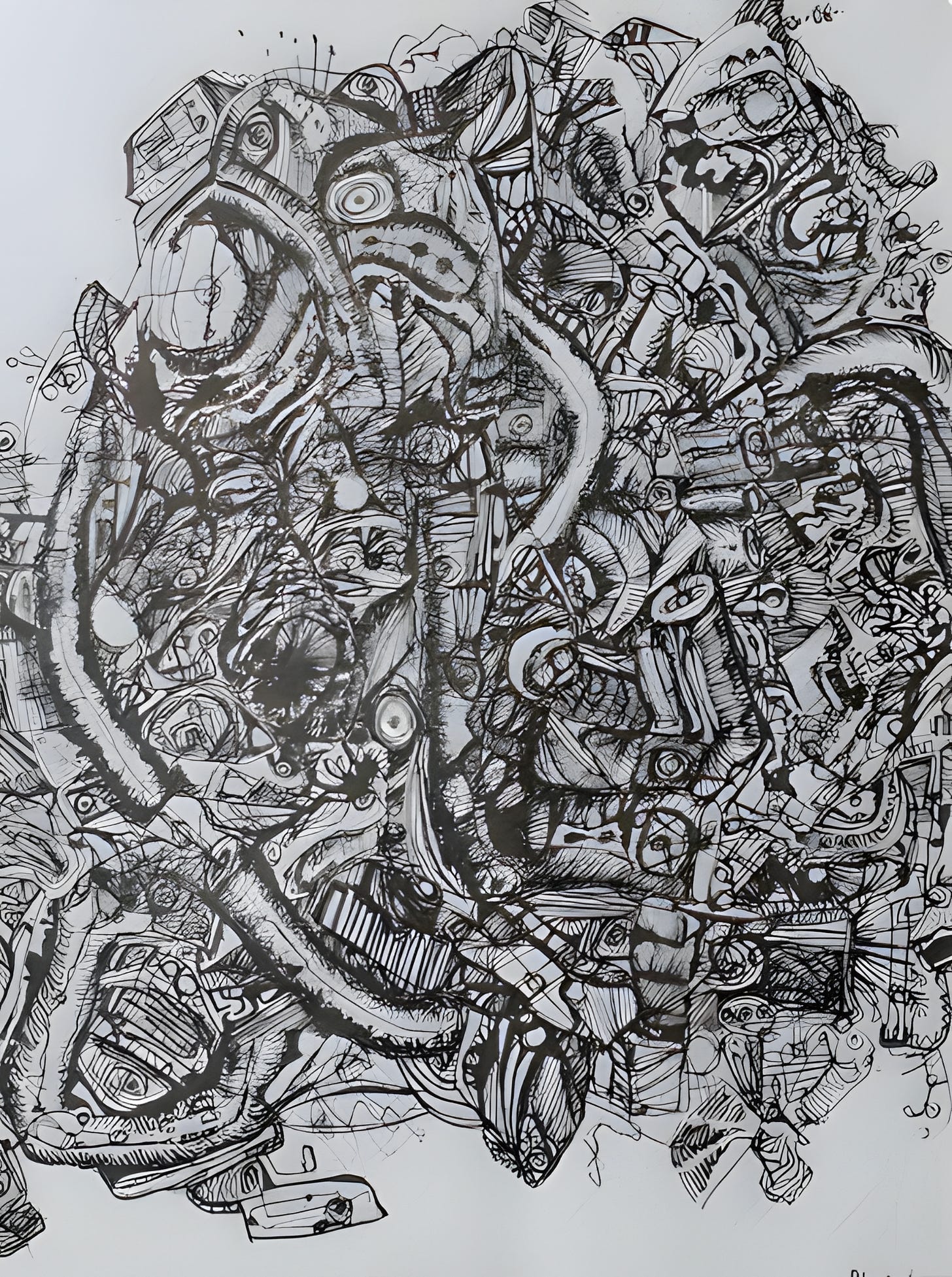

Here is the Junkheap as it is recapitulated in the hypermodern art of Mary Church in her Atrocity (2006):

And her Red Junkheap from around 2008:

According to the Kabbalistic myth, the wholeness of Creation can only be repaired through a tikkun olam (or “world mending”) that will restore its fundamental unity and integration through the processes of world-historical Events.

And that is the task of Hypermodernity. For whereas Modernity is Integral and Postmodernity is Dis-integral, Hypermodernity is Re-integral. And that’s what its Ur-symbol, The Multiverse, is all about.

But we’ll get to that next time.

It's just a metaphor for the type of transformation of the harnessing of electicity that goes on with each epoch.

Could you explain body electric? I don’t quite have a handle on it. I kind of follow, but I want to be sure