On the Hypermodern Crisis of Meaning

Hypermodernity began, as I wrote back in March of 2018 on my blog cultural-discourse.com, in 1995 when the National Science Foundation turned the Internet over to the public. Hypermodernity is, therefore, the generation of the millenials, and it is a generation which is particularly anxious about meaning. It is not a generation that is concerned with irony, sarcasm or the Derridean play of significations that mocks the very process of meaning-making in the metaphysical age (as defined by Heidegger) from Plato to Nietzsche. It is Nietzsche who begins the deconstruction process and warns—especially in his notebook The Will to Power—that the coming consequences of European nihilism will be dire. And he was right: the World Wars erupted just after his passing.

However, there were plenty of great metaphysical thinkers during Modernity, thinkers who painted on huge canvases (like Picasso) with Big Ideas that attempted to create what I call “apparatuses of semiotic capture” in which those ideas were captured, nailed down and placed inside huge cathedrals of ideas, such as Alfred North Whitehead’s Process and Reality; Teilhard de Chardin’s The Phenomenon of Man; Sri Aurobindo’s Life Divine, and so on. Plenty of meaning-making going on in Modernity.

But all of that was wiped out at the end of World War II with the detonation of the atom bomb in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, at least on the physical plane. On the cultural plane, the art of Mark Rothko (shown above), with its luminous squares of light in the late 1940s and early 1950s captured what Derrida called a decade later the “absent ontological center” at the West’s heart of Being. Derrida began as a Heidegger and Husserl scholar and he specifically meant that the West’s idea of Being had collapsed in on itself and so there were no longer any ultimate transcendental signifieds—such as God, the Subject, Freedom, etc.—to anchor the play of signifiers so that they did not skid around and collide into each other, causing semiotic chaos.

That is precisely what happened with Postmodernity, of course, of which Derrida was one of the key architects, along with Foucault, Deleuze, Baudrillard and company. There was no such thing as meaning any longer. That was regarded as outdated and antiquated. Foucault announced, in the introduction to The Archaeology of Knowledge, that philosophy would only be concerned henceforth with micro narratives. And Lyotard, in The Postmodern Condition announced the death of all grand metanarratives. Those days were over. No more Big Picture thinkers like Oswald Spengler or Arnold Toynbee. (Cultural historians like Joseph Campbell were dismissed as intellectual colonializers).

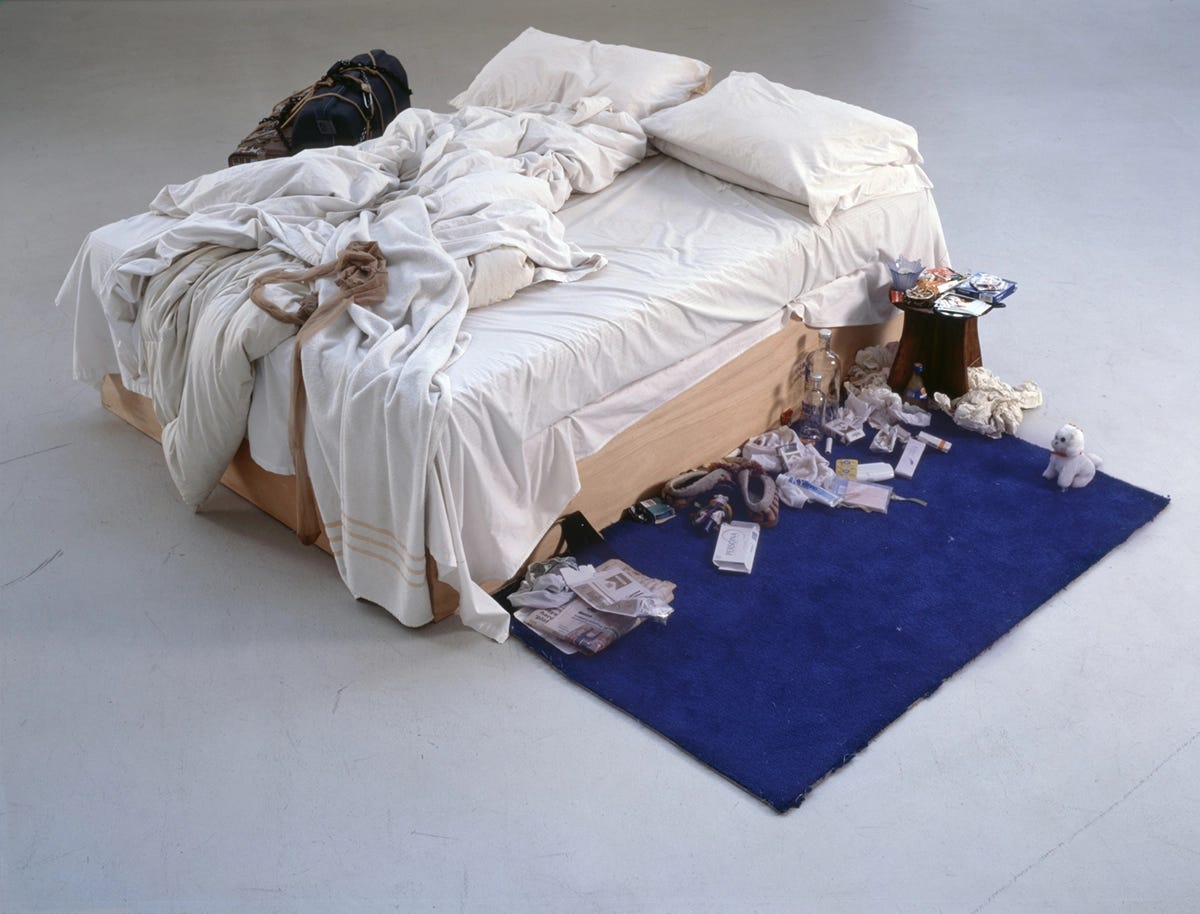

And consequently postmodern art—also known as “contemporary art”—slid into semiotic chaos with Tracy Emin (“My Bed” is shown below), Damien Hirst, the Viennese Actionists, Gerhard Richter, Josef Beuys, and so on. Contemporary art was—and still is—a disaster in which it became fashionable to mock the very process of meaning making in art. Andy Warhol, Bruce Nauman, Jenny Holzer: all were parodists of the very idea that art should mean anything at all. (Consequently, not many people like it).

But then 1995 came along and the Internet exploded on the scene as a new apparatus of semiotic capture that engulfed all previous forms of media into a new world interior. As McLuhan pointed out, the content of any new medium is an older medium. The content of the printed book is the illuminated manuscript. The content of film is the novel. The content of television is radio. And so on. But within the Internet, the content becomes all preceding forms of media of communication since the days of the cuneiform clay tablet. It is a monstrous medium, an aberration, that melted down all analogue media: shopping malls, books, records, newspapers, magazines, celluloid, darkroom photography, und so weiter. They now exist only inside the Internet. (Its hubris even demands a capital “I”).

The Internet created an entire world age, namely Hypermodernity, in which the subject now exists only as a deworlded entity removed from the context of all locality and concrete existence within a particular World horizon. On the Internet, we are all being accelerated to lightspeed which, as Einstein famously pointed out, causes time to stop, flattens objects into two dimensionality and confers upon them infinite mass. In the Internet we are all flattened, made into instantaneous entities and are colliding with one another like particles in a particle accelerator.

Hence the crisis of meaning which plagues the millenial generation: does any of this mean anything? The crisis was kicked off in 1999 with the Columbine shootings—the first mega spree killings—by two kids who were completely haunted and confused by the meaningless suburban landscape in which they found themselves. So desperate were they for meaning that they turned to Nazi rhetoric and ideology, itself the violent product of a meaning crisis that hit Germany after their loss in World War I.

The psyche, you see, needs meaning just as much as your body needs food, sex, shelter and clothing. Confronted by a massive theater of digital semiotic vacancies, the psyche goes into chaos mode and increases violence. Hence, our current age of social chaos on the Internet, where everyone hates everyone else. As McLuhan said, “violence is a quest for meaning,” and he was one hundred percent correct.

Hence the return of the Big Thinkers, who now appeal to this generation very much: Oswald Spengler, Martin Heidegger, Carl Jung, Arnold Toynbee, etc. etc. The current generation of millenials does not share the previous generation’s scorn of grand metanarratives. Today, it is the very opposite. They are hungry for them because they are hungry for meaning. A meaningless world, after all, is a meaningless thing. Of what use is it?

Something similar happened in ancient Rome after the Punic Wars (264-146 BC), which were their equivalent to our World Wars. They emerged from their victory over the Carthaginians and became the undisputed great power of the ancient Mediterranean world, just as America emerged out of World War II as the Great Power of the global world. But beginning with the public assassination of the tribunate of the plebs, Tiberius Gracchus in 133 BC (analogous to the Kennedy shootings; Tiberius’s brother Gaius was also assassinated about ten years later), Rome at that point turned from big wars with external enemies to social and civil wars within the supposed “zone of cooperation” of Roman society itself. We know how that ended: with the erection of the Caesars who built the Roman Empire and brought a Pax Romana within Rome (though not for the unfortunate barbarians in the hinterlands).

That age too suffered from a crisis of meaning in the arts and in philosophy, a crisis that began during the Hellenistic epoch in which art there too (shown above) mocked the process of making anything mean anything. The answer to this semiotic chaos, though no one saw it coming, was the erection of a gigantic apparatus of semiotic capture through the maximal stress event of the crucifixion of Christ and the birth of Christianity that soon followed.

This is where we’re at now: it’s important to have “maps of meaning,” such as Spengler’s Decline of the West or Toynbee’s A Study of History, to tell us where we’re at. Once you know where you’re at, it gives you some idea of where you’re going. Of course, history does run in spirals but it also has unique singularities, such as the Internet, which is still new and very uncertain territory. We don’t know where this medium is taking us. It is still too new to know for certain.

But I will say one thing: it cannot be an accident that all of the current social chaos that is taking place coincides with its advent. The Left has become a caricature of itself, the party—no longer—of tolerance, but of intolerance of social differences and values, while the Right, bizarrely, has become the party of tolerance. How the fuck did that happen?

It is precisely the Internet that has done all this with its collapse of time and space which is forcing everyone to collide with everyone else. There’s not enough breathing room in here. It is a well known fact, both in human society and in populations of animals, that crowding increases violence.

But it is meaning, on the other hand, that settles it down. For myself, I have returned to the very ancient religions of astrology and reincarnation which, as far as I am concerned, are simply facts. The old dying religions that are currently crumbling all around us did get some things right: India got reincarnation right and the Babylonians got astrology right. But Christianity, though it brought about the triumph of the City of God, missed the boat on reincarnation and made the mistake of returning to a flat earth cosmology. It is a cosmological atavism.

Science, in turn, has gotten quite a few things right. But it has completely missed the boat on higher dimensions and planes of non-physical existence of souls waiting for more bodies to hop into (which is why the sex drive in humans is so high). Science breeds atheism as a matter of course and it is fundamentally nihilistic of all values. It may create great technologies, but it could care less about the ethical and social consequences of those technologies. Those are simply unforeseeable.

But Science doesn’t care. This is the first civilization in history to remove all taboos—every single one of them, as the genetically engineered virus out of Wuhan shows—in the pathway of that march of Progress known as “knowledge.” Except that this is only knowledge of the physical world. Of the metaphysical world—which is real and actually exists—it knows nothing and treats with scorn and derision anyone stupid enough to be concerned with it.

But it is precisely the metaphysical world that confers meaning upon human life and gives the psyche orientation in time and space. From the viewpoint of the spiritual world, everything means something. Nothing at all is random. Not one single thing.

How long can this nihilism continue?

The Singularity, I’m afraid, is indeed near.

One of the best pieces of yours I’ve ever read.

Very good article. I have one small challenge. Science has one faith-based value: That is is always better to find more stuff out.

This might seem like a given, but I'd argue that in most other world views there are forbidden types of knowledge. Christianity developed the concept of knowledge that is 'satanic' or 'sinful' for instance.

To add a couple of ideas I think that the meaning crisis is being in part caused by the death of futurism. Environmental concerns such as rising temperatures, soil degradation and ocean plastic (it's more than just 'global warming') have shown everybody that technology alone will not lead us to a utopian future; the dream of the modern age since the early 1800's.

On the other hand, medicine and human rights have increased life spans and prevented high mortality rates of infants, women in childbirth and men (and women, but mostly men) in dangerous jobs. This means that for the first time in human history up to half of women are not having kids (and often having kids close to age 40 when they do).

This is unprecedented. Women throughout history had to, on average give birth 7-9 times. No wonder, relieved of that biological obligation people are now often at a loss as to what to do with their lives. Say what you will about the burden of children, they do make the parents lives about something.

Creative people have other outlets. They reproduce through ideas art and ambition.

Most people are not creative though. So they look for ideologies to fill the meaning void, and we simply don't have an overarching ideology that's good enough yet.

So people spring from one to the other: Vaccine mandate protests, Trump, woke, alt-right, etc. The details are not important. The underlying mass emotional pattern is. The meaning crisis will continue until one or more geniuses brings a bout a spiritual, emotional paradigm shift.