Simon Stalenhag is a Swedish contemporary pop artist (now in his early 40s) who in 2015 published the first volume of his Tales from the Loop series (the fourth volume, The Labyrinth, was released in 2021). It was made into a (not entirely relevant) Amazon streaming series in 2020, and the third volume, The Electric State, has been adapted by Netflix for its own series to be released in about a week (March 16, 2025).

Stalenhag is an artist who draws his influences primarily from pre-production film artists like Ralph MacQuarrie and Doug Chiang, Syd Mead and the sci-fi / fantasy / horror illustrator Michael Whelan.

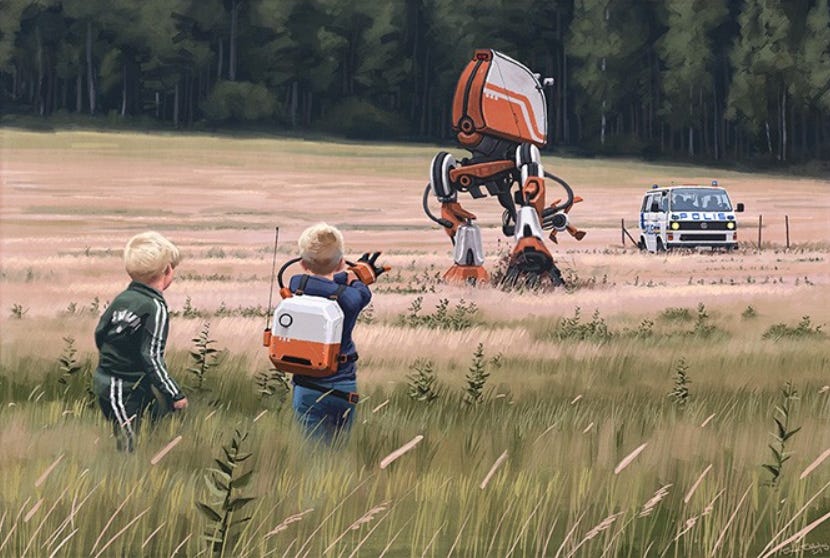

Stalenhag’s premise in Tales from the Loop involves the fictional creation of the world’s largest particle accelerator in Sweden, built underground and loosely modeled on the famous Hadron Collider in Geneva, Switzerland (hence “the Loop”). The reader / viewer does not know for sure, but somehow the collider has been involved with a cosmic catastrophe that has created a post-apocalyptic society living in 1980s-style Swedish suburbs where rogue robots escaped from failed experiments wander the countryside.

In an episode entitled “Remote Glove,” the mischievous narrator (who is remembering himself as a child from an adult’s perspective) recounts how one day he and his friend discovered a robot under a tarp in a garage and then when they found the remote glove that operates it, set the robot roaming across the countryside under the boy’s own (misguided) will.

The individual episodes, though all set within the same premise, are strangely disconnected from each other and Stalenhag wisely leaves it up to the reader to fill in the gaps. His work is an example of what Marshall McLuhan called “cool media” in the sense that—like comic books—they are low resolution and therefore invite high participation on the part of the viewer or listener (in the case of jazz) to fill in the gaps. Stalenhag gives a short one page extended narrative caption to each image that doesn’t explain the image but rather evokes it.

Thematically, Stalenhag is asking questions concerning what Peter Sloterdijk calls “monstrous technologies,” such as genetic engineering, artificial intelligence or nuclear power, any one of which technology contains the potential to end life on this planet. I think the case could be made for particle colliders to fall into that same category too. Stalenhag evokes its monstrosity with images like these…

…of cooling towers which resemble cosmic sentinels that dwarf the human being to the scale of a mere insect. Is human life even possible, let alone worthwhile, when technologies on such a colossal scale are every day calling upon vast universal forces from the cosmos, forces that render him entirely beside the point?

Stalenhag is a master of the kind of minimalism which implies or suggests rather than pointing directly. For instance, notice that the company name on this heavily industrialized dock is “Nibelungen,” a direct reference to Wagner’s epic ring cycle, Der Ring des Nibelungen, another kind of “loop,” a mythical one which also runs round in circles.

So the Loop, the particle accelerator, goes through a series of semiotic transformations in the reader / viewer’s mind. It is at once the ring in Wagner’s opera which brings about a cosmic collapse with the Ragnarok of the fourth opera, Die Gotterdammerung, in which the universe is consumed by a conflagration; but the Loop is also a possible reference to the earth’s Van Allen belts, the two “loops” which surround it with a torus made out of protons and electrons that protect it against the solar wind.

But, as we have said, myths run round in circles, too. Jean Gebser’s mythical consciousness structure, in his 1949 classic The Ever-Present Origin, is also circular and polaristic. Indeed, myths in general repeat their themes over and over again like the recurring cosmic manvantaras of Hindu mythology, of cycles within cycles within cycles. Stalenhag has brought into focus with his art (deliberately) vague narratives of the end of the cosmic cycle of a blown-out civilization that, like Atlantis, was once technologically sophisticated but now leaves its membra disjecta haunting the countryside with hulking wrecks of industrial steel skeletons and rusting metal carapaces which once, perhaps, housed monstrous intelligences.

Stalenhag thus places us within Spengler’s future timeline when our Faustian civilization will lie, as he says in Man and Technics, “in fragments, forgotten – our railways and steamships as dead as the Roman roads and the Chinese wall, our giant cities and skyscrapers in ruins like old Memphis and Babylon.” If Stalenhag is not familiar with Spengler, it doesn’t matter because he shares the same Germanic world view that is skeptical of all things Anglo. Every Scandinavian simply presupposes Ragnarok as part of his built-in world picture.

The Ur-symbol of hypermodernity, we might say, is the Multiverse, for the ontological a priori of any truly hypermodern narrative—be it pop song or Netflix streaming show—is a metacosmic reality of planes within planes within planes; of astral beings and multiple dimensions; of parallel universes folded one within another. This is also the a priori assumption that Stalenhag makes, for the particle collider, somehow, has ruptured a loop in time so that a portal to the Jurassic era is opened up and dinosaurs straight out of Jurassic Park are loose all over the Swedish countryside.

Thus, multiple temporalities, multiple universes, folding one within another, is an absolutely skeletal characteristic of hypermodernity. This Multiverse no longer fits within the quaint little box of Christian angels, Ptolemaic spheres and heavenly saints. This universe—or rather Multiverse—is way more complex, and way more bizarre, than anything that our little high octane chimp brains can ever fully comprehend. All of the artists, poets and filmmakers of hypermodernity presuppose such a spiritual cosmology whether we are talking about a man who gets lost in alternate dimensions inside of his own house (Lost Highway and Danielewski’s House of Leaves), or the astral body time-traveling in William Gibson’s science fiction novel The Peripheral; or the multiple planes of etheric energy presupposed by Willow in any give song on her Ardipithecus album.

Of course, the dinosaur as a signifier brings along with it an apocalyptic connotation of a coming cosmic catastrophe, but with Stalenhag’s imaginary landscape the temporality of the dinosaurs is enfolded within a previous industrial civilization which already lies in ruins while its fellaheen inhabitants scramble across its remains like ants disassembling the corpse of a dead animal.

At one point, a child has climbed into a kind of sonic sphere which opens a portal for him to enter a small town in the American Southwest in which yet another gigantic and monstrous particle collider exists. Multiple realities, multiple temporalities, multiple universes. That is the common unifying Ur-symbol for hypermodernity.

Stalenhag, wisely, never tells us exactly what has happened to this civilization. Instead he just leaves haunting signifiers that move the viewer’s field of concern into certain nervous directions. An anxiety regarding all things technical, especially those on the scale of “monstrosity,” permeates the entire (loosely disjointed) narrative. Stalenhag’s extended captions for each image (which are mini-narratives unto themselves) act like the libretti of opera or the lyrics of pop music in that they are merely illustrations of the images. Stalenhag thus reverses the typical illustrated narrative like Alice in Wonderland or Stephen King’s Dark Tower series, in which the illustrations are mere decorations for the text. For Stalenhag, it is the other way around.

There will also be inevitable controversy when it comes to Stalenhag’s technique, which constitutes a reversal of the traditional role of the artist as creating three dimensional canvases in physical space which can then be shown during an exhibition, because in Stalenhag’s case, there are no original paintings since he is composing them entirely with computers. They have no external correlates in that rapidly vanishing Gutenbergian Galaxy in which all cultural products, be they books or canvases hung on the walls of a museum, must be considered as ontologically “there” in physical space in order to be considered “real” works of art or literature. Thus, by the rules of the traditional academy, Stalenhag’s work could never be considered “real art.” Its ontological status could only ever be considered (at best) a phantasmatic Baudrillardean hyperreality.

Under the conditions of hypermodernity, however, all the traditional rules of the status quo in the academy are being rewritten by what I have termed in my 2011 book “the new media invasion” of digital technologies. I foresee many Walter Benjaminian debates taking place between media theoreticians such as Byung-Chul Han and Peter Sloterdijk concerning what constitutes “real art” and “non-real art.”

What the academy and the high finance world of art commerce do not realize is that the laws of the media—as McLuhan called them—are always changing and are always being recreated by artists and technological geniuses like Steve Jobs and Elon Musk. Artistic geniuses do not follow the rules, but rather make them (for everyone else to follow).

We’ll create the new laws of the hypermodern mental phase space.

Just watch us.

Baudrillard's hyperreality is part of the postmodern Junkheap insofar as it involves the creation of simulacra of historical realities such as Disneyland's spatialization of time in which past epochs like The Old South which are put side by side with Smalltown, America or Futureworld. The 1972 version of Michael Crichton's Westworld does exactly the same thing whereas the HBO version of it is hypermodern in that it presupposes the hypermodern ur-symbol of the multiverse.

well written... The techno dystopia Mark Fisher talked about of endless recreations as fiscal policy would not allow for the expense of art that takes time to develop in its own anarchic process.

"as McLuhan called them—are always changing and are always being recreated by artists and technological geniuses like Steve Jobs and Elon Musk"

The endless tirade of narratives created by perception managers, children of millionaires that sold a new format and not a new idea.

No wonder everyone is left disappointed that creative work is still secondary in a world full of overabundance to the point of tariff wars?

Existential inflation of the product forgot to allow new movements and narratives to appear. Ergo

the rebellion will not be lives streamed or a.i produced.